On September 15th, Guatemala celebrated its 196th anniversary of independence—and our school joined in! With two parades, a special assembly and a school-wide breakfast (and a day to recuperate afterwards), our students performed their civic duties with aplomb.

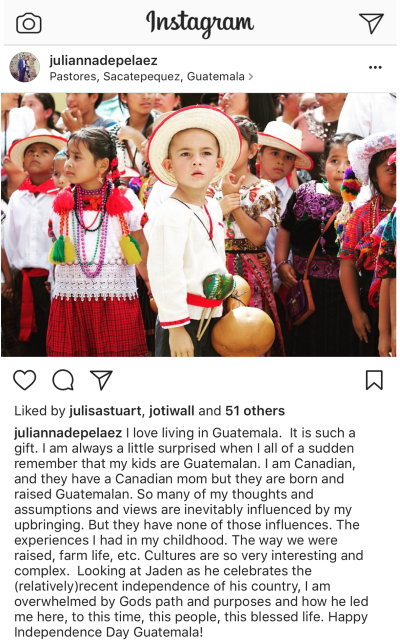

During the first parade, our youngest students were asked to dress in traje típico (“TRA-hey TEEP-ee-co”), traditional Mayan clothing, as part of the civic celebration. This típico clothing varies from region to region, so some of our students are dressed in the fashion of their parents’ region, but most are dressed in clothing typical of the Kaqchikel, the Mayan people group most represented in our area.

Elena, one of our host moms in Tizate, is a proud K’iche’ (Quiché), as is her husband. When groups come to their home for lunch, they often find themselves up a precarious staircase behind the dining room, dressed in elaborate, hand-made, brightly-coloured skirts and blouses, hearing her husband speak about the pride of the indigenous people. The traje típico of Guatemala is unique: each area of the country has different patterns, colours and dress, and this is celebrated as part of Guatemala’s unique heritage.

Before the Spanish conquest of Guatemala began in the 1520s, there’s no historical record of these vibrant and diverse clothes, but as the conquistadors established their hold in the areas that would become Guatemala, the traje típico slowly emerged as a measure of control. The colonized indigenous people were essentially enslaved, restricted to a particular town or region, and if an indigenous person’s clothing immediately identified them as a worker from Panajachel, Quetzaltenango or Escuintla, it was quickly impossible for indigenous people to flee from the oppression of the conquistadors.

Guatemala is like this: everywhere you look there is beauty and great difficulty, national pride mixed with loss.

Almost five centuries after the Spanish conquest, traje típico is celebrated as a unique and beautiful part of Guatemalan culture. Guatemala is like this: everywhere you look there is beauty and great difficulty, national pride mixed with loss.

Traje típico is one of the things that sets Guatemala apart, but woven into its history is the subjugation of the indigenous people of Guatemala, and almost five hundred years of suffering, punctuated with natural disasters and violence.

In modern-day Guatemala, the use of traje típico diminishes. There are families like Elena’s, who hold fast to their traditions and teach their children the K’iche’ language. In a tourism-focused city like Antigua, few people on the streets wear traje típico—unless you wander into the local market, where almost every vendor is dressed in traditional clothing.

The Guatemalan flag features the country’s coat-of-arms. The scroll in the center bears the date of Central America’s independence from Spain (September 15th, 1821) and two crossed rifles represent the willingness of the Guatemalan people to fight for their independence. Two crossed swords represent honour, a quetzal (Guatemala’s national bird) represents liberty, and the laurel crown, victory.

Carlos Castañeda, a local agronomist who has studied Guatemalan history at length, suggests this shift has several causes. The oppression and difficulties of the indigenous people leads to a history that some would like to forget, while it’s an integral part of Guatemala’s story. For instance, kids will often say to each other “no seas indio”—literally, “don’t be Indian”, but figuratively, “don’t be stubborn or foolish”. In Guatemala, this is neither racial slur nor compliment: it’s simply what you say.

Castañeda also suggested that traje típico is less common because of cheap used clothing that comes from America and is sold in pacas (markets) throughout Guatemala. The influence of North American culture is growing, too, as legal and illegal immigrants in the United States and other nations remain connected to their families, sending money and other goods back home. “Even in the smallest village in Guatemala you can find a guy dressed like a New York gangster,” Castañeda added.

Our prayer is that, with eyes wide open to what has happened, our students will move forward, establishing the Kingdom of God wherever they go.

For our students who march in traje típico, we hope our celebrations will educate them about the past of their country while maintaining our school vision. During our assembly, students read Scripture and made prophetic declarations over their country, and we prayed as a school for God’s blessing to be on Guatemala. Our prayer is that, with eyes wide open to what has happened, our students will move forward, establishing the Kingdom of God wherever they go.

Leave a Comment